Features

Opinion

Producing the results your policing agency needs through continuous improvement: How to stay efficient while reducing costs

June 23, 2023 By Bill Cooper and Terry Anderson

Money got tight and we were forced to make adjustments. From a management perspective, we needed to look at how we were performing and what we needed to improve. To do that we examined ourselves in terms of two essential issues: 1) Money suffocates creativity, and 2) Leadership is tested by necessity.

We were challenged by both. Previously, our budget hadn’t been much of a concern and we didn’t spend time considering the consequences of an economy that wasn’t in good shape. We were a government agency and we thought funding would always be there, even if we may not always agree with the level of funding.

The new, reduced budget wasn’t going to meet our needs and we needed to figure out how to better ourselves with the resources we already had. We didn’t want to cut key services; at the same time, dispatching officers to calls for service that were better handled by the community itself, was a poor management approach.

By evaluating our department using the thought that money suffocates creativity/the capability to strategize potential solutions, we opened the department to input. We discussed the thought that leadership is tested by necessity, and found ourselves to be a well-intended, hardworking agency that was almost totally reactive in nature, not proactive.

Our evaluation showed we could do many things better—we needed to improve, and not in just one area. We moved to apply successful and proven business skills. We needed to stop reacting and instead prepare for what the present and future would bring. We re-developed the model and created a management system that worked in serving and partnering with the community, always producing measurable results.

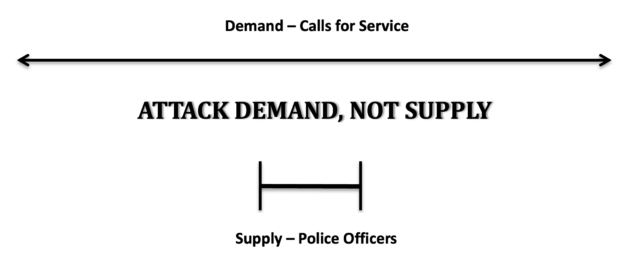

We applied business principles and looked at ourselves as a service organization; we work from a supply and demand perspective, where demand continues to grow and the supply to meet it doesn’t. What was, and is, happening is that demand continues to grow and the supply of officers doesn’t. We don’t look at demand and, in many cases, allow problems to manage us rather than us managing the problems.

Credit: Bill Cooper and Terry Anderson

Further, when there are budget reductions, we cut staff and services aligned with our mission. We continue to grow demand by adding responses to many services and calls that are not aligned with why the department exists. The system is and remains out of balance.

Continuous improvement

As we re-developed the department, we adopted the philosophy of continuous improvement. Continuous improvement is the ongoing effort to improve services and processes through incremental and breakthrough strategies.1 It’s a method for identifying opportunities for streamlining work and reducing waste.2

We built a robust, graphics-rich business intelligence system, useful for deploying resources to identifiable problems. We modified community-oriented policing with a highly successful community investment model. This model was designed to work with each neighbourhood to resolve many minor community concerns that they were more capable of handling. This was designed to reduce the ever-growing demand of calls for service officers were responding to that the neighbours could do themselves. By reducing this demand, existing officers could be re-deployed to true mission-oriented activities. Demand was reduced, and the department optimized the resources it already had.

We also adopted Lean Six Sigma to find the real causes of problems, to no longer attack the symptoms of those problems. It proved to be a great addition to managing the department and its structure. Incredible results were achieved financially, politically and culturally with significant time savings and cost avoidance.

Efficient systems and processes

The need for more efficient and effective systems and processes continues to grow in virtually all organizations. The public sector, including law enforcement, finds itself under increasing demand to reduce cost and increase service.3 Lean Six Sigma is a method used to identify waste in a system that doesn’t add value, and to increase the speed to completion, reduce time and cost and increase quality of all work. This was one of the primary motivators for the department to move to business principles such as this.

The final element of the business model we created was to define the department as a value proposition. We receive millions of taxpayer dollars chartered with public safety and quality of life, so we asked ourselves if we were providing at least that much, or more, in terms of measurable value. We were able to determine how to quantify value and changed our entire reporting system where we showed results rather than just activities.

Based on what we learned, we began to view how we led the department and changed our philosophy to a far more effective and efficient approach to policing. We give our leaders the ability to forecast and prepare for what the department will look like in one year, two years, three years. As retired California Highway Patrol Captain Gordon Graham said, “if you can predict it, you can prevent it”. If we can forecast where law enforcement is going in general and at a local level, we can act in a very proactive manner and further enhance community quality of life and departmental credibility, internally and externally.

Because these changes required definitive leadership skills for 21st century law enforcement, what does the research show us? I met Dr. Terry Anderson, PhD, a pioneer in law enforcement leadership development, and spent considerable time with his work, and with him in person. Anderson is a long-time leadership development expert.

Anderson has created continuous improvement teams both in Canadian and American law enforcement agencies. Even with documented successes, there are departments that decline to change their management systems for a variety of reasons; “We’re too busy getting the job done and our people don’t have the time to fill out forms or track numbers or statistics” is one example. Getting departments to change from tradition is often more difficult than one would imagine.

During my time as chief, my team and I formed continuous improvement teams using the doers; the team was chartered to develop continuous improvement and sustain it. They created policy and procedure for continuous improvement and assured that department leadership bought into the program and supported it.

Given the changes we were making, we encountered predictable obstacles we needed to overcome, such as:

- Change: we introduced new methods, such as Lean Six Sigma, changing the way we did things, redeploying staff and involving key people in helping build continuous improvement. There was resistance to overcome, and we did in most cases.

- Organized labour: some union members believed we were going to cut union positions to fulfill financial requirements by using these new programs. We didn’t.

Many staff and employees didn’t believe we could achieve what we were talking about—but we did.

To overcome this resistance, we had to market the new programs and methods; we needed to show them we were making their work better, faster and at a higher quality. We had to show them results.

The need for more efficient and effective systems and processes continues to grow in virtually all organizations.

We also convinced organized labour that we were not cutting positions; rather, we were reducing waste, redundancy and re-works, which ultimate saved time and costs. We removed the problems that consumed resources but added little to no value to what we were doing, and the officers were focused on doing police work.

The reality was that if we wanted people to buy into what we were doing, we need to let them help us build it. This has worked pretty much everywhere and will continue to work, essentially because people want to be part of something special, and certainly want to be recognized for their efforts.

So, what did we achieve, in addition to faster results with lower costs?

- Streamlined processes

- Optimized staff and resources

- Freed up considerable time, allowing existing staff and resources to concentrate on real growth and development

- Improved individual and department performance

- Reduced attrition dramatically—we were the organization others wanted to work for/with

The best outcome we achieved was that we moved from a reactive, activities-based model to a proactive, problem identification, results-based model. We defined the organization as a value proposition, giving the community real value for the dollars invested in the department. We took supply and demand and attacked demand (volume) rather than supply (staff and resources).

By using a combination of business principles, and by creating continuous improvement teams, the department realized almost immediate relief from many of its concerns. The outcomes from a budgetary/financial perspective are significant, as demonstrated in the case study briefings that follow. From an internal and external political perspective, the benefits tell an enviable story, and the internal and external culture of the department has brought improved performance, measurable outcomes, reduced attrition rates and align with and reportable results.

Case study

The Greater Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Police Department and hospital serves veterans of the armed services and is the largest in the United States, with 110 buildings on 880 acres. There are over 5,000 employees and an 81 person police department, handling high volumes of violence, loss and disorderly conduct incidents.

The new police chief brought me to the department to teach these management models and implement them. The results achieved by the department can be accomplished by any organization choosing to provide its community and local government with real, measurable outcomes.

- Overtime cost reductions in the first year from $489,000 to $164,000, a reduction of $325,000 annually – a 66 per cent reduction in cost.

- The department was on target to reduce overtime from $164,000 per year to $72,000 per year.

- Total reduction in less than 2 years of 85 per cent.

- Security officer contract at the Veterans Hospital on the campus reduced from $2,200,000 to $1,400,00, a reduction of $800,000 annually – a 36 per cent reduction in cost.

- The department was on target to reduce contract costs even further the following year, from $1,400,000 to $975,000.

- Total reduction in less than 2 years of 57 per cent.

- Full time employee (FTE) reduction (through attrition) based on mathematical approach to staffing from 81 to 70 FTEs, a cost savings of $674,000 annually.

- Total dollar savings to date = $1,799,000.

- Crime Statistics from primary crimes:

- Physical assaults reduced by 40 per cent

- Thefts reduced by 26 per cent

- Disorderly conduct incidents reduced by 59 per cent

- Prior to the introduction of these models, the department had the worst scores for VA police services in six out of eight categories, with an overall rating of being the worst among the 18 different service lines combined.

- By using these models and leadership development skills, the department had the same scores as the VA facility leader in four out of the eight categories, and above the mean average in all eight categories.

Law enforcement leadership demands a review of contemporary policing practices and a move towards management more aligned with practices that bring the right results while also enhancing the quality of life in the communities they serve.

References

- American Society for Quality (ASQ). “Continuous Improvement.” http://asq.org/learn-about-quality/continuous-improvement/overview/overview.html

- LeanKit, https://leankit.com/learn/kanban/continuous-improvement/

- Cooper, William E. Leading Beyond Tradition: Exceeding Expectations in Any Economy. 3-Star Publications, 2012.

Chief Bill Cooper (ret) is a 30-year law enforcement award-winning veteran who teaches, trains and consults with law enforcement organizations. Cooper is a graduate of the Command College and FBI National Academy and holds an MBA and second master’s degree in Public Administration. He is also a Lean Six Sigma Master Black Belt and has trained several hundred departments.

Dr. Terry Anderson serves as the Chief Leadership Officer at the International Academy of Public Safety in North Carolina and is the President of Anderson Corporate and Executive Coaching, Inc. in British Columbia. He coaches and advises police executives mainly on the west coast of the U.S. and Canada. ConsultingCoach.com.

Print this page