Features

Better budgeting: Finding better and more efficient ways to do business

May 25, 2023 By Brittani Schroeder

Photo credit: FERGREGORY / Adobe Stock

Photo credit: FERGREGORY / Adobe Stock In today’s society, the police have been increasingly responsible for much more than the core functions of public safety. Officers are now expected to solve a variety of problems that develop in the community, from resolving noise complaints and reversing overdoses, to de-escalating behavioural health crises. This change in the ever-expanding role of the police also raises questions on how policing agencies are supposed to fund these tasks, investigations, mental health calls, and more.

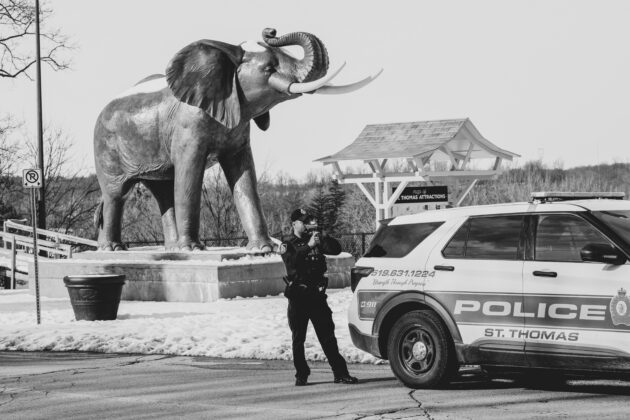

Blue Line was able to speak with Chief Marc Roskamp of the St. Thomas Police Service and Chief Mike Callaghan of the Belleville Police Service to see what is costing their police services the most right now, and what can be done when looking at sustainable funding models for the future.

The highest price tags

When looking at what is costing police services the most money, technology is at the top of the list. “Modern technologies are a requirement for a modern public safety service provider. To provide adequate and effective policing services that address the deeply rooted social challenges and pressures present today, police personnel at all levels must be equipped with the tools to do the job,” says Chief Marc Roskamp. These modern technologies include, but are not limited to, digital evidence management and associated storage requirements, body worn cameras, modern training systems, equipment and platforms, and digital forensics.

Police departments have quickly realized that as the technology in the communities increases, so too does the challenge of keeping on top of that technology within the world of policing. “As our personal phones and other devices get more complicated, we know that practically every criminal investigation that surrounds a harassment, an assault or intimate partner violence, involves a production order for a personal device,” says Chief Mike Callaghan. “In order for our forensic digital examiners to be able to open up those devices to extrapolate the information required for the investigation, they need the proper equipment, and so you can see how our costs have gone up exponentially just in this one area.” Chief Callaghan also states that these increased costs can be significant, especially for the small and mid-sized police agencies.

This is where Chief Callaghan would like to see more interoperability opportunities with surrounding agencies, to see if there is the ability to share a cooperative licence as opposed to individual site licences for this equipment. As an example, Belleville is surrounded by Ontario Provincial Police detachments. “If we could share what we have with them, and they with us, it would significantly benefit both services,” he says.

Another area where costs have gone up is for police mental health training and resiliency resources. “Due to the evolution of society, the increasing aggression towards the police, and the social and health-related challenges public safety personnel have been faced with over the past several years, we are seeing members struggling more and needing to take a break from their roles for indefinite periods of time. At the end of the day, police officers and police support staff are human beings, and the polarization of society asking the police to be all things has reached a boiling point,” says Chief Roskamp.

In his opinion, Chief Roskamp believes that as the police must continually re-evaluate their roles in challenging community matters, there needs to be broad collaborative approaches with key community stakeholders so that police services can return to public safety obligations. Key partners must be funded and resourced to step up in ways that have not been seen in the past. “Reframing the delivery of human services is required. To continue on a path of accepting responsibility for the wide ranging social and health challenges that are increasingly expected to be a police response, will have detrimental effects to police members—both sworn and civilian. Although the police will always step up and do the right things to support their community, there are costs associated to prolonged systems and approaches that simply are not within the purview of our sector. Burnout is real and it is costly,” he says.

Photo credit: St. Thomas Police Service

Effective ways of doing business

To find better, more effective ways of doing business in the policing world, Chief Callaghan believes that police services need to look beyond interoperability. Chief Callaghan explains that there are a few large police organizations across the province of Ontario that serve the largest municipalities. These departments have in-house lawyers, psychologists, psychiatrists and statisticians on staff, and when you look at adequacies and effectiveness of policing standards, Chief Callaghan believes that these larger services can provide those standards a lot more than a smaller or midsized police agency. This applies to being able to support victims of crime, but also the ability to support the police members.

Chief Roskamp believes that there are always ways to reimagine and find efficiencies within policing. He says, “Police services that are serious about finding new solutions and stretching budget dollars are recognizing that some traditional sworn roles can be accomplished by skilled civilians.” This itself helps to lower costs in some areas and reallocate the funds elsewhere.

When searching for sustainable funding models down the road, Chief Callaghan believes Canada should look no further than England, where the funding dollars for policing actually comes from the federal budget perspective.

“Right now, we get provincial funding grants, and the provinces do a wonderful job at providing grants for specific positions within the department—for example, funding human trafficking or child exploitation investigators. But what happens is those grants may be around for three to five years, and then those grants are no longer available, and the municipality is responsible for funding them. As you can imagine, it becomes incredibly expensive,” explains Chief Callaghan.

“At the end of the day, the community deserves to be safe and feel safe, and a highly trained, skilled and healthy team is essential to the delivery of services that are expected by the community.” – Chief Marc Roskamp, St. Thomas Police Service

On the topic of proactive policing, Chief Callaghan suggests that police services need to look at the way they’re providing proactive policing. “We need to look at it in a whole different context moving forward,” he states. As an example, he shares that 15 years ago, there were very concentrated efforts and educational opportunities when it came to impaired driving. Officers were giving presentations in the high schools, and they saw a real decrease in the number of impaired drivers on the road. Now, police are seeing a rise in the number of sexual assaults and intimate partner violence, and Chief Callaghan believes that the officers need to get back into the schools and start up that education piece again.

This proactive policing piece, coupled with keeping up with the standards of policing that are available to large organizations that have significantly bigger budgets, is going to be a real challenge for small and mid-sized police agencies in the next five to seven years, says Chief Callaghan.

Photo credit: Belleville Police Service

A future of sustainable funding models

In Chief Callaghan’s view, policing is going to change more in the next seven to 10 years than it has in the past 100 years. The reason for that is accountability and ensuring that every single community has the same resources available to them. “It doesn’t matter who you ask, young people or old; they will tell you that we all have lost the element of accountability for ourselves, and the challenge of holding that accountability together to ensure the moral fabric of the community is intact falls on the shoulders of the police. This means we’ll also need to look at policing through the lens of adequacy and effectiveness. All of this stems from a sustainable funding model for policing, whether it’s through federal, provincial or some other kind of funding.”

For Chief Roskamp, a future sustainable funding model is a model that recognizes that safe and healthy communities can be achieved when strong public safety services are in place. Additionally, it is imperative for community partners to be well-resourced and appropriately funded so they may support the community from their sector. “It must be about robust multi-sectoral approaches that involve key leaders throughout the community. We all need to work together to close the gaps in the human, health and social services sector, and to provide proper pathways to meaningful healthcare so that individuals are not falling vulnerably into the criminal justice system. For those that willingly decide to offend against society, they will be held accountable for victimizing innocent communities. If these areas are strengthened – it will contribute greatly to improved and sustainable funding models for police services.”

Editor’s note: Are you a member of police leadership and would like to weigh in on this topic? Please reach out to bschroeder@annexbusinessmedia.com to continue the conversation.

Better funding models for police means policing initiatives, like those in the photos below, can continue. Thank you to St. Thomas Police Service and Belleville Police Service for the photos.

- AED Frontline Donation. Photo credit: Belleville Police Service

- 2022 Polar Plunge. Photo credit: Belleville Police Service

- 2022 Cops & Kids Fishing Derby. Photo credit: Belleville Police Service

- 2022 Cops & Kids Fishing Derby. Photo credit: Belleville Police Service

- 2022 Shop with a Cop. Photo credit: Belleville Police Service

- Photo credit: St. Thomas Police Service

- Photo credit: St. Thomas Police Service

Print this page