Changes to the frequency of income assistance payments and greater oversight of recovery houses could significantly reduce overdoses and property crime, according to a study in one of Canada’s opioid hotspots.

Published in February 2019, a report from the University of the Fraser Valley in B.C. scrutinized where and when opioid overdoses and deaths (OO&D) and property crimes took place from 2016 to 2018 in Surrey, B.C. The city of about 550,000 in the Metro Vancouver area has the second highest OO&D rates in B.C, which in turn has Canada’s highest OO&D rates.

The timing and locations of more than 5,100 OO&Ds and 32,000 property crimes – juxtaposed against 68 recovery house locations and income assistance payment dates – were studied in Predicting Illicit Opiate Drug Overdoses in the City of Surrey: Impacts of Opioid Use in Neighbourhoods by Paul Maxim, Len Garis, Joseph Clare, Hubert Duan and Andrew Fink.

It was the first published study in Canada that pinpointed small geographic areas to illustrate the impact of opioid use on individual neighbourhoods, as opposed to cities, regions or provinces.

Key findings from the research revealed:

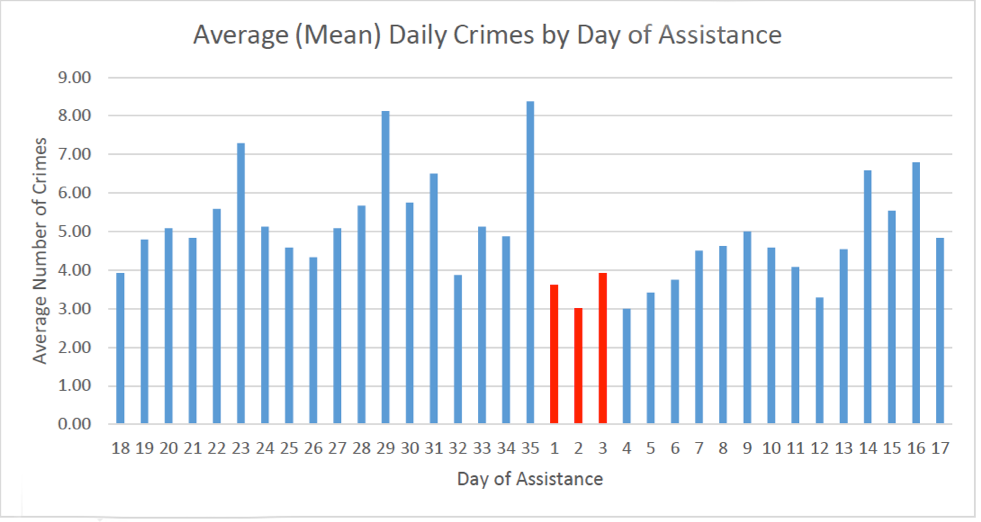

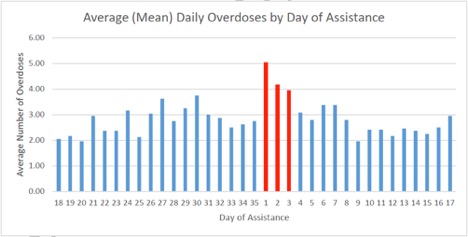

- Within three days of income assistance cheques being distributed, daily overdoses were 37 per cent higher and daily property crime incidents were 15 per cent lower than during the rest of the month.

- There is a clear city-wide pattern of people receiving income assistance cheques, using them to buy drugs, and then turning to property crime when they run out of money.

- Recovery houses are at the epicentre of this activity. About 70 per cent of reported overdoses and 90 per cent of overdose deaths occurred within 500 metres of a recovery home in 2016 and 2017. The effect of income assistance cheques on property crime was also more pronounced in neighbourhoods with more recovery houses.

- Predictive analytics show promise in helping to more accurately forecast future overdose incidents.

“The data clearly illustrate the endless cycle of opioid addiction, social assistance and property crime that is playing out in communities across the country,” noted Maxim, the lead author. “It also shows us how we can interrupt that cycle, in order to save lives and reduce the societal costs of property crime.”

A closer look at recovery houses

The 68 recovery houses identified in the study included 55 formally registered through B.C.’s Assisted Living Registry and 13 with no government oversight. The city has also identified a further 90 “nonrecovery houses” that are essentially lodging for addicts with no on-site staff and minimal—if any—services.

In B.C., recovery houses receive government funding to provide housing, food and services to individuals with a substance abuse addiction, but they are not held to the same standards as treatment centres. Even at the licensed sites, the living conditions, services and resident monitoring can vary significantly from one to the next.

A strong relationship exists between illicit drug use and recovery houses – sometimes referred to as a “chicken and egg” situation. Agencies tend to locate recovery houses where potential clients are located, and at the same time, the houses become magnets for users seeking assistance.

Based on the research, Surrey Fire Services and a local health nurse conducted “soft interventions” of known recovery houses, including health and safety inspections, distribution of additional naloxone kits, and staff training. It was noted that although 93 per cent of the houses had naloxone on site, 73 per cent did not have a staff training regimen.

A retrospective analysis of the impact of these measures, based on previous statistics, did not provide conclusive results.

However, the authors noted that the study’s findings suggest that expanding the outreach role of recovery houses could have an impact on OO&Ds in the surrounding neighbourhood.

The “cheque effect” on overdoses and crime

The authors also examined the relationship between OO&Ds, property crime and dates of income assistance payments in Surrey, building on an existing body of research that shows relationships between the timing of the monthly cheques with overdoses (the so-called “cheque effect”) as well as property crime.

The rationale is that the cheques provide drug-using recipients with funds to support their addictions, leading to increased overdoses. As the money runs out, they resort to crime.

Surrey’s OO&D data was overlaid with property crime data – specifically, business and home break-and-enters, shoplifting, and vehicle thefts. From October 2016 to October 2018, there were 5,171 overdoses and 32,454 crime incidents in Surrey, an average of more than seven overdoses and 45 property crimes every day. Each set of data was also divided into two date groups: within three days of cheque issuance, and the remaining days of the month.

Two types of testing showed a statistically significant relationship exists between the dates of income assistance payments, overdoses and crime incidents in Surrey. Around the days when cheques are distributed, overdoses are significantly higher and property crimes are significantly lower than during the rest of the month.

Further testing also revealed links between cheque issuance and the locations of property crime and recovery houses.

To provide a fair representation of the community as a whole, the authors took a closer look at seven neighbourhoods in Surrey with varying concentrations of recovery houses, property crime and overdoses. They found the “cheque effect” on overdoses and crime was present throughout, but was more pronounced in areas with more recovery houses.

This was more starkly shown in the north Surrey neighbourhood with the highest concentration of both recovery houses and overdoses. In the three closest days to cheque issuance, overdoses there averaged four per day, 43 per cent higher than the 2.6 overdoses per day during the rest of the month. Likewise, there were 3.4 daily crime incidents in the area in the three closest days to cheque issuance, which is 48 per cent less than the five daily crime incidents taking place during the rest of the month.

Even when all seven neighbourhoods are compared, the data shows a clear pattern.

Leveraging data to save lives

Working with Microsoft and its Azure Databricks cloud computing analytics platform, the researchers also examined if daily overdose incidents could be predicted with any degree of certainty.

Predictive modeling techniques were applied to data from October 2016 to August 2018 related to the north Surrey neighbourhood with the highest concentration of overdoses, with parameters including season, month, day of the week, day since last income assistance payment, property crime incidents (particularly shoplifting), and crime and overdose incidents for the previous day, two days and week.

The resulting algorithm was then applied to incidents during September and October 2018, and found to be slightly over the actual result, with an error rate of 1.13. Given the average of almost three daily overdoses in the target neighbourhood and seven across the city, the authors determined this to be a significant accomplishment.

The timing of overdoses and income assistant payments, along with day of the week and time of day, were identified as being among the most important predictive factors. The results are worthy of future development and expansion, the study said, and could be used as a starting point for data-driven discussions on how to enable responders to be more proactive on overdose events.

The ability to even marginally increase the accuracy of overdose predictions could enable responders to provide advance educational treatments, drop-off naloxone kits or have ambulances ready for response in high-risk areas.

The report concludes with the following policy recommendations:

- Launching a pilot project increasing the frequency of social assistance payments to weekly or biweekly, to level out the spikes in overdoses and property crime.

- Increasing the number of safe injection sites to make regulated supplies of opiates available to addicts who are not ready to make the transition away from street drugs.

- Increasing the role and responsibility of legitimate recovery houses beyond their immediate confines, including improved staff training.

- Regulating “nonrecovery” houses to enforce health and safety standards at minimum, and ideally encouraging services such as counselling and availability of naloxone.

The social implications of opioid dependency, and drug use in general, go well beyond the impact on individual users: addiction affects the entire community. As new information becomes available, it is critical that decision-makers interrupt the cycle wherever possible with data-driven interventions.

The study can be downloaded for free from the UFV public safety and criminal justice research database at https://cjr.ufv.ca.

Len Garis is the fire chief for the City of Surrey in British Columbia, an adjunct professor in the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice and an associate to the Centre for Social Research at the University of the Fraser Valley. He is also a member of the Affiliated Research Faculty at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York and a faculty member of the Institute of Canadian Urban Research Studies at Simon Fraser University. Contact him at LWGaris@surrey.ca.

Print this page