Features

Corrections Corner

Managing radicalization in Canadian prisons

September 16, 2019 By Elina Feyginberg

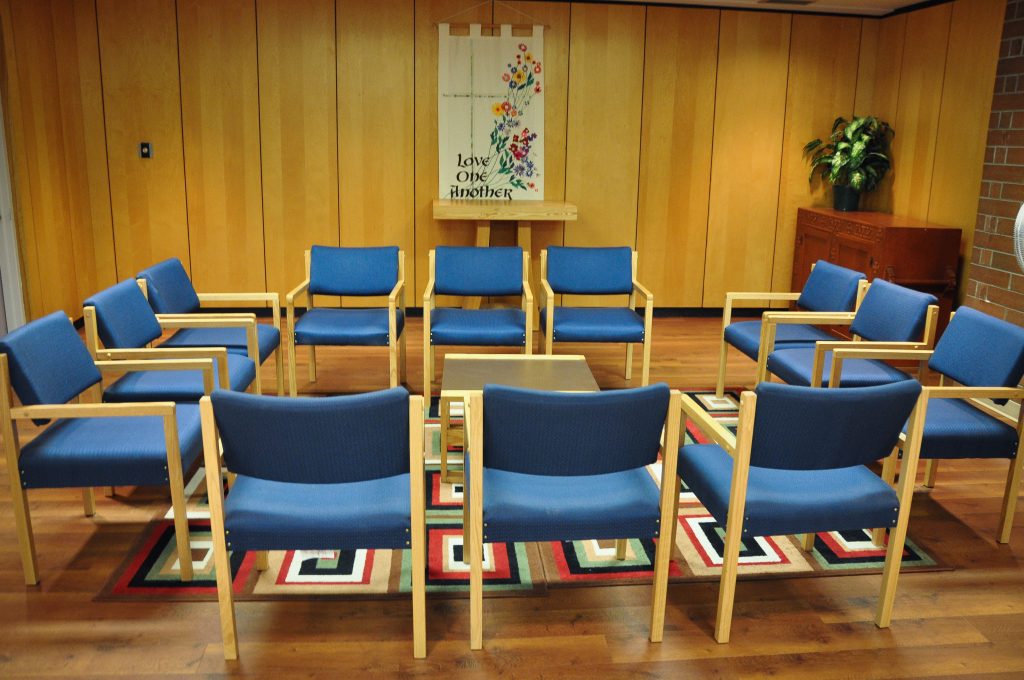

The Chapel at Kent Institution. Photo via Flickr, Correctional Service Canada.

The Chapel at Kent Institution. Photo via Flickr, Correctional Service Canada. Radicalization in Canadian prisons is a wide spread occurrence, although one that has not been widely researched or studied by the Canadian correctional system.

“More Canadians have been imprisoned on terrorism-related crimes in the past 18 months than used to face such charges over decades,” reported Alex Wilner in the article, “Getting Ahead of Prison Radicalization,” published by the Globe and Mail on Oct. 18, 2010.

With homegrown terrorism happening here in Canada, the population of incarcerated terrorists has also increased. Although incarcerating terrorists is a good idea, there is also a significant risk of potential recruitment and radicalization that could spill over to the general offender population.

Several models have been studied and developed in Europe and the United States that focused on dealing with radicalization in prisons. Canada’s correctional system should follow the approach of their European and American counterparts with respect to developing similar strategies.

Past practice in Canadian prisons has always been to segregate and isolate high-profile, radicalized offenders. A great example of that practice was the 2006 arrests of a number of the so-called Toronto 18 terror group members, who were segregated throughout several Ontario institutions. The idea of such segregation was to ensure safety and security of all, as well as to prevent potential recruitment and radicalization of other offenders in custody.

The practice is one of the few preventative techniques still used in Canadian prisons, however, with the upcoming changes in regards to eliminating segregation in Canadian prisons, and the move towards the Structured Intervention Units, the risk of recruitment and radicalization among prisoners will potentially increase.

“On June 21, 2019, Bill C-83 – An Act to amend the Corrections and Conditional Release Act and another Act received Royal Assent,” the government announced. “In particular, the amendments to the Correctional and Conditional Release Act (CCRA) in this bill eliminate administrative and disciplinary segregation, and introduce a new correctional model including the use of structured intervention units (SIUs) for inmates who cannot be managed safely within a mainstream inmate population.”

The infrastructure changes, policy development and staff hiring and training is anticipated by November 2019.

“Inmates in SIUs will have the opportunity to spend a minimum of four hours a day outside their cell. This includes two hours per day to have meaningful contact with others including other inmates, program and parole officers, Elders and chaplains,” the feds stated on Aug.29, 2019.

As positive as such interactions may prove to be to the offenders’ mental health, it also opens up the door for increased opportunity of recruitment and radicalization by those who otherwise would not have access to such an opportunity.

Several studies on inmate trends and behaviour have noted that much or radicalization in prisons happens as a result of the need for camaraderie or the need for protection. These same studies have also noted that offenders, as a general rule, are rebellious and reject authority. Such behaviour makes these offenders more prone to becoming radicalized and adopting extremist behaviour.

“Prisoners are in close proximity to others looking for camaraderie or common ground. They are often rebellious and reject authority, society and the system. If they are not well-versed in religion, they can also be open to converting to extreme interpretations of Islam, [according to Dr. Wagdy Loza, a psychiatry professor at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont.],” reported Kathleen Harris in her 2015 CBC article, “Radicalization a growing risk in Canadian prisons, experts warn.”

It is important to understand and differentiate between someone who converts to Islam in order to find peace and religious values, and someone who adopts the extreme interpretation of Islam, which can lead to radicalization in some cases.

Having several qualified Imams visit the institutions, conduct religious programming and screen for signs of radicalization is only one of the strategies adopted by European correctional model to prevent radicalization in prisons. Some others include:

- ensuring literature and messages promoting radicalization do not get into prisons

- developing programming to de-radicalize and reintegrate offenders back into society

- supporting non-government organizations and other groups that facilitate ex-radicals’ integration into mainstream religious communities

It is not an easy job to track and prevent radicalization in prisons. The Canadian correctional system needs to invest more resources into research and programming to ensure that the matter does not become a serious national security concern.

Print this page