Features

Health & Wellness

Opinion

A culture of openness: dissolving the need to be “invariably invulnerable”

A career in law enforcement is undoubtedly highly stressful with an elevated risk of experiencing life-threatening situations, traumatic incidents involving violence, fatal accidents and other death scenes.

November 15, 2018 By Isabelle Sauve

As such, should we draw a parallel between this highly stressful work environment and the recent tragic, self-inflicted deaths of a number of Canadian police officers (five in one month in Ontario alone, according to the Police Association of Ontario)? What are the contributing factors to suicide in our police forces? More importantly, how can the number of these tragic occurrences be reduced?

Several research studies from the early ‘60s in the U.S. were adopted by other countries (including Canada) and supported the notion that the rate of suicide was higher with police compared to the general public. It was therefore logical to assume that the stress encountered by police was a trigger to suicide.

Conversely, new research has highlighted this difference between police and the general population actually fades due to the particular demographic characteristics of police forces. Indeed, the majority of officers are male (around 80 per cent) and in their early 20s to late 40s. This is the population in general with the highest risk of suicide.

Unfortunately, the data related to first responder suicide is not widely available in Canada in order to draw similar conclusions. Much of the data is actually gathered anecdotally, we have discovered, and not independently validated.

Whether or not the rates are equal or higher than the general public; it is interesting to consider how police officers who undertake a thorough selection process designed to identify the most psychologically and mentally fit for duty, who have access to well-paying and meaningful work with numerous benefits, are still in distress — given these are characteristics usually related to low suicide rates.

Based on this, one should ask what is contributing to suicide within Canadian police agencies? The factor most likely to be suggested is the strong negative effect of trauma encountered while on duty, which has the potential to lead to a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Without minimizing PTSD as a cause of suicide, more recent research highlights law enforcement officers can also be highly affected by repeatedly facing unhealthy tasks. These practices slowly erode mental and emotional health and include (but certainly are not limited to):

• undertaking work for which officers are not adequately trained

• shift work

• bureaucratic management styles

• insensitivity to personal distress

• inappropriate, arbitrary and unfair management ruling

• lack of consultation with personnel

• increased workload due to low workforce

• erratic work hours

• repetitive tasks

• lack of long-term planning, resulting in shifting priorities

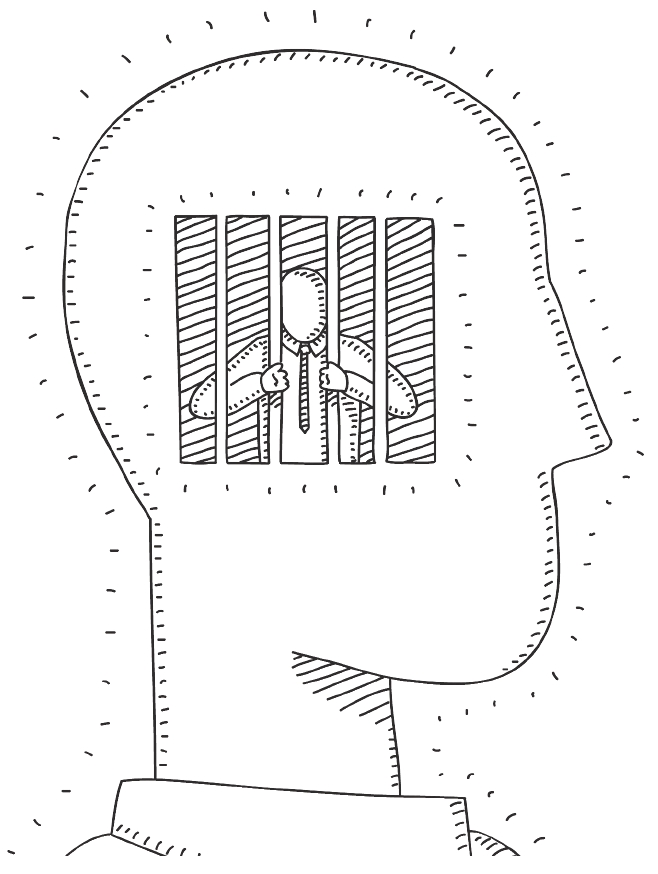

Furthermore, the culture of policing in general discourages admission of distress and emphasizes what many sociology experts describe as “macho problem-solving,” which includes a need to be “invariably invulnerable.” Consequently, law enforcement officers will fear admitting to personal anguish as it may destroy their reputation and potentially their career.

However, in light of increased understanding through recent studies surrounding mental health and suicide, it is critical to abolish a culture where individuals remain silent on these matters out of fear of negative repercussions. The unrelenting grind of stressors and exposure to abnormal situations can wear away at even the toughest officers. It can be likened to getting thousands of paper cuts, each delivered one by one, some stinging more than others. The accumulation of repeated and seemingly smaller stressors can be as devastating as exposure to larger scale or more obvious traumatic events, especially when they are combined. Everyone is unique in terms of triggers, response, perception and tolerance threshold.

European studies highlight the quality of treatment received by distressed or traumatized individuals from an organization “strongly mediates the impact of trauma and the likelihood of suicide. In essence, negative treatment of a traumatised individual by an organization compounds the effects of trauma – making suicide more likely.”

Assuming there is a link between all the above factors — recurring trauma experienced, repeated lower-level stress, and the way in which distressed officers are handled by organizations — they all must be acknowledged and addressed with the implementation of appropriate mitigation strategies.

Despite efforts by police services to implement responsive wellness strategies and assistance programs with access to health professionals, the effort largely focuses on major trauma and PTSD. It is crucial to apply more holistic and aligned strategies that account for shortcomings.

As such, our Canadian police forces must have a plan to educate its personnel and treat it as its most valuable asset. Managers must be appropriately trained to respond adequately to distressed colleagues, encouraging a culture of openness about mental health issues and removing unhealthy stigmas.

Isabelle Sauve is a 11-year OPP veteran currently with the Emergency Response Team (ERT) at the Almaguin Highlands Detachment in Burks Falls, about 300 km north of Toronto. She can be contacted at: isabelle.sauve@hotmail.com.

Print this page