Features

Behavioural Sciences

What is psychosis? – A primer for police officers

January 2, 2020 By Dr. Peter Collins

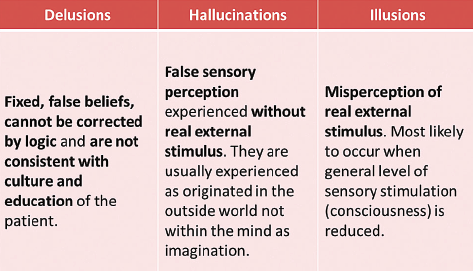

Psychosis is a term that denotes a disorder of thought. By definition, a disorder of thought involves tangential thinking and difficulty in maintaining thought on a fixed topic. Typically, there are two major components – delusions and perceptual abnormalities.

Delusions

Delusions are false, fixed and formed ideas that are inconsistent with the accepted beliefs of a person’s education, culture or social background. The false belief is held with extraordinary conviction and subjective certainty. Delusions are the world view of those who experience them.The most common delusional themes are paranoia; grandiosity and religiosity.

Paranoia involves intense anxious or fearful feelings and thoughts related to persecution, threat or conspiracy. Paranoia occurs in many psychiatric disorders, but is most often present in psychotic disorders. Paranoia can become a delusion when the irrational thoughts and beliefs become so fixed that nothing (including contrary evidence) can convince a person that what they think or feel is not true.

A person with grandiose delusions has an over-inflated sense of worth, power, knowledge or identity. Others may believe that they have a special relationship with someone who is famous. The person might believe he or she has a great talent or has made an important discovery. Delusions of grandeur are more common with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. If a person has a history of bipolar disorder and has had delusional thoughts in the past, delusions are more likely to happen again.

Hallucinations

Perceptual abnormalities are hallucinations. Although hallucinations can be in any sensory modality – sight, hearing, taste, smell or touch — auditory and visual hallucinations are most commonly experienced in psychiatric conditions. Gustatory (taste), olfactory (smell) and tactical (touch) are less common in major mental illness but can be experienced in other medical conditions.

When confronting someone with a disorder of thought, officers should ask if the person is hearing voices and if the voices are telling him or her to harm him/her self or others (command hallucinations).

An illusion is not a hallucination; it is a misperception of physical phenomena that is external to the person. While they can be disturbing in some situations, illusions are not due to internal beliefs. They are tricks of the eye.

Psychosis

The classic disorders that involve psychosis are schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and delusional disorder. These are deemed to be serious mental illnesses because of the major impact they cause on life and relationships. In addition, psychosis can be experienced by people with other diagnoses, such as major depression and bipolar disorder.

Officers should also try and determine if the psychotic individual is using drugs or alcohol. Individuals with schizophrenia, as an example, are at a higher risk for suicide, especially if they have a co-existing diagnosis of substance abuse. Another cause of a psychotic state is drug-induced psychosis. On a regular basis, frontline officers and police crisis negotiators encounter individuals who are psychotic and potentially violent due to their consumption of agents like methamphetamine and THC.

For the frontline officer who encounters a psychotic individual, it is important to acknowledge that the subject has delusions but not to argue, agree or disagree with the delusional beliefs. It is also crucial not to deceive or lie to the subject. Don’t pretend that the delusions are true or you can hear the voices as well. Although they may be delusional, the individual will remember being deceived and this will make their co-operation less likely in subsequent encounters.

In trying to determine the content of the delusions, those subjects who experience the delusional belief of control by an external force (an override delusion) are more at risk for violence as are those have the delusional belief of infidelity. If present, these delusions may double the risk of violence but overall those who experience these symptoms will not be violent.

Generally speaking, psychosis is weakly associated with violence. Certain symptoms, and not a particular psychiatric diagnosis alone, are associated with violence. Overall, the risk of violence is still better predicted by being a young male than by a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The combination of schizophrenia and substance abuse have higher rates of violence than those with substance abuse alone, who, in turn have higher rates than those with schizophrenia alone.

In conclusion, psychosis is a symptom, not an illness. Given the uniqueness of this state, its widespread relevance and its potential destructiveness, it is important for those in law enforcement to understand and empathize with those individuals who are suffering from a psychosis.

Dr. Peter Collins is the operational forensic psychiatrist with the Ontario Provincial Police’s Criminal Behaviour Analysis Unit. He is also a member of the crisis/hostage negotiation team of the Toronto Police Service Emergency Task Force. His clinical appointment is with the Centre for Addiction & Mental Health in Toronto, and he is an associate professor with the University of Toronto. Dr. Collins’ opinions are his own and may not reflect the opinion of the OPP, University of Toronto, CAMH or his mother. Contact him at peter.collins@utoronto.ca.

Print this page