Features

Opioid crisis leads to updates in K9 training

Earlier this year, 12,000 fentanyl pills in B.C.’s Fraser Valley were taken off the street thanks to a newly trained nose for narcotics. The credit goes to RCMP police dog Doodz, who found the drugs in a car pulled over for speeding — the first dog in Canada to detect fentanyl after updated training in the spring, according to police.

September 8, 2017 By Renée Francoeur

Almost all 173 RCMP narcotics-profile dogs across the country have now been imprinted for fentanyl.

Almost all 173 RCMP narcotics-profile dogs across the country have now been imprinted for fentanyl. It’s nothing new that crime isn’t as cut and dry as it once was — for example, technology has made fentanyl, carfentanil and other opioid strains more accessible and the internet has taken DIY explosive making to a new, frightening level. This ups the demand on K9s and leaves little choice but to refurbish their training procedures.

Drugs & drones

Jason Gunderson, president of the Canadian Police Canine Association (CPCA), says K9 training has stayed “fairly consistent over the past five-10 years.” Changes in training are usually a result of trial and error, he says, and entail “building on a foundation that we know works.”

“We have seen the re-emergence of the use of food as a primary reward system, basing it around marker training, which has resulted in clear communication between the handler and the dog,” says Gunderson, who is also a dog handler with Regina Police Service in Saskatchewan.

While the programs at RCMP’s Police Dog Service Training Centre (PDSTC) in Innisfail, Alta., were operating at a high level, they were also fairly stagnant for about a decade, according to head trainer Staff Sgt. Eric Stebenne.

“But for the last two and a half years, we’ve been very proactive in our approach and in modernizing quite a few of our programs,” he says. “We’ve made major changes or additions to the fentanyl detection program and are in the process of modernizing explosives detection. We’re also going to roll out a new human remains detection program this fall.”

The CPCA is currently looking at the best practices for training of police service dogs in the detection of fentanyl, too.

“Fentanyl is a concern to the CPCA as it brings with it a number of questions around training and if this training should occur,” Gunderson says. “This crisis, if you will, is one in which the CPCA will continue to monitor, but at the same time we have to apply concern towards our partners and determine what the best practices are for all the stake holders involved.”

Meanwhile, a police and military K9 training company based in Beeton, Ont., has begun adding robots and drones to its training curriculum, in order to “keep officers safer and away from threats,” according to Tony Pallotta, head trainer at Working K9. But he says it’s “too early” for fentanyl to alter Working K9 training programs just yet.

“How easily absorbed fentanyl is puts the dogs in a dangerous situation,” Pallotta elaborates. “Officers have brushed up against it and ended up in an overdose situation. It’s really difficult at this point to say how training for this could go for us. Having Narcan [an opioid antidote] on hand is one change that’s important.”

Deadly odour

Fentanyl is an especially hot-button topic when it comes to public safety, as well as the wellbeing of a force’s four-legged friends.

This was the focus of one session during the CPCA’s 2017 conference in Springbrook, Alta., this past June, a “refresher course” and space to share knowledge for officers and their dogs on things like high-risk vehicle stops and various emergency response situations.

Edmonton-based CTOMS Inc., a military training company, presented on how to manage and treat fentanyl exposure for both handlers and dogs, says Cpl. Daniel Block with Red Deer Provincial Police Dog Service, who helped organize the CPCA seminar.

“We all carry Narcan and the dosage for the dog is quite a bit higher than for humans, so it’s important to know exactly how to administer that,” Block says, adding that CTOMS also reiterated how crucial it is to monitor your dog after a drug search — “if they get some on their paws, the only way they have to clean themselves is to lick it off.”

The key to the dog’s safety is to take preventative measures, says Block, whose partner is a five year-old German Shepard named Eve.

“Today, drug searches have many more precautions.”

Stebenne says RCMP quickly realized fentanyl would only become more prominent due to its attractively low price tag (in comparison to heroin) and the fact that all you need is Wi-Fi to find it.

“People still ask why we got involved with fentanyl if it could potentially kill or harm our dogs. Do we stay in narcotic detection or get out of it, then? That was the real question and the answer was clear — we’re police officers, of course we stay in it,” Stebenne says.

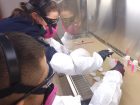

Seeking a safe way to introduce fentanyl detection to the dogs, the training centre partnered with the B.C. RCMP crime lab team and developed a program that involves the drug in a diluted liquid, keeping the dogs safe from inhaling airborne particles. This was then tested in the centre’s search room where the odour is isolated from the dog as well as the person.

“In addition to that, we then developed safe practices. All of our trainers and handlers are equipped with naloxone spray, masks, gloves and safety glasses,” Stebenne says.

Almost all 173 RCMP narcotics-profile dogs across the country have now been imprinted, he notes, with the rest set to finish the program by the end of summer.

Since the new training was launched this past February, PDSTC has received numerous requests for information from law enforcement agencies across North America.

To meet this demand, 35 participants from Canadian, American and Mexican law enforcement agencies gathered earlier this summer to learn RCMP methods for the mixing of the liquid form and to understand expected dog behaviour in the presence of fentanyl.

Stebenne notes there have already been a few K9 fentanyl detection successes on the West coast.

“It’s been very rewarding to see our initiative has improved things,” he says, while pointing out that, to his knowledge, not a single RCMP dog has been severely impacted by fentanyl to date.

“If and when we have to administer naloxone to a dog, it will be a bit of a rodeo. If the dog is very alert, I can see them not enjoying having their nostrils sprayed very much, but hopefully that doesn’t happen.”

According to Stebenne, the force is now closely following W-18, an opioid strain “100 times more toxic and potent than fentanyl,” and can add that to the narcotic detection program safely if needed.

“All the groundwork that Eric has laid out, the addition of safety protocols and equipment, and changing the mindset of the dog handlers in the field on how we do business — that has made us better equipped for the next big thing, whatever that may be,” adds Chris Browne, another trainer at PDSTC. “So if it is W-18, we really feel confident that we have the safety and training capability to get those odours safety imprinted to our dogs. It will just be a matter of determining what concentration is safe for the dogs.”

The ‘homemade’ component

Fresh challenges have presented themselves for K9s trained in the explosives profile as well.

The Royal Newfoundland Constabulary’s K9 unit follows the RCMP training standards and programs, according to Sgt. Russ Moores, and is well suited to difficult crime-solving tasks required in all of the province’s green space and rural areas.

Moores was the handler of the first explosives detection police dog at RNC, Rocky, who started back in 2006 and retired in 2013. Today Moores works the beat with Rocky’s grandson, Dyson.

Up until recently, Dyson was the only explosives trained dog but RNC now boasts two in the four-dog unit, Moores says, in response to demand.

“The way the world is today, the things we see in the news — explosives are talked about a lot, and we have an international airport here as well as a busy port, so the need for explosives dogs comes up quite a bit,” Moores says.

“When we assist at the ports or airport, it’s more of a screening to ensure [explosives] are not there. We have had cases of where explosives have been stolen and our K9 teams have had to search for them,” he says. “Our port is busier and busier, with oil traffic and cruise ship traffic has increased, too. The ports have their own security protocol but we’re part of it… Ten years ago I was hardly ever there. Now we’re down there multiple times a year to help out.”

With the RCMP set to update explosives training, Moores says he’s looking forward to seeing how that goes, in terms of speaking to challenges like finding everyday, household materials in homemade bombs.

“We really had to adapt to current stress,” Browne with the RCMP says of the explosives portfolio. “We’ve learned from what is taking place all over the world over the past decade and adapted our explosive detection program to meet the current stress but that’s all I can say about it.”

Pando Stepanis, a master trainer with the National Association of Professional Canine Handlers and who runs Olympus K9 in Ontario, agrees that training has to become more innovative.

“We have kids mixing up TATP (triacetone triperoxide), a peroxide based explosive because there’s simple recipes for it all over the internet,” Stepanis says. “This is extremely dangerous.”

Human remains

“Over the years, there have been several successes with our dogs finding human remains,” Browne says, and though unsure of the exact number, predicts there have been hundreds of these cases. “We’ve always relied on the assumption that once trained, our dogs and handlers would have the ability to locate human remains but without having a real set of standards or something to measure, like we do with every other program.”

The PDSTC, partnered with the Nova Scotia chief medical examiner’s office, is now formally introducing a human remains detection program in the fall.

“The medical examiner has been gracious enough to offer us human remains through an existing donor program,” Browne notes. “This was key to the development of our training.”

Most of the new training will be done on site in Innisfail, thanks in part to PDSTC purchasing an additional 22 acres.

“We have 173 teams across the country but determined there is no need to get every team trained in human remains detection,” Browne adds. “We’ll partner with several PDS (police dog service) co-ordinators who will conduct an analysis and let us know how many teams they need per province or division trained, and then we’ll be in a position to actually begin.”

Other departments in the country have had smaller programs in relation to human remains detection but as for one that will have a national impact, this will be a first, he says.

“It’s pretty exciting for us and we know it will bring value to our programs and to divisions, municipalities, provinces and give us an enhanced ability to go out and help locate remains and bring closure to families.”

No matter what type of enriched training regime is required, K9 safety remains top of mind, as not only are these animals skillful force multipliers, they are also beloved partners.

“It’s said we spend more time with our dogs than our families,” Block says. “That’s 100 per cent true.”

Print this page