Features

Maximizing de-escalation

Police use of force events that result in injury, particularly when a subject is suffering from mental health crisis, often makes headlines, usually with little context, about what may have occurred. Significant events can impact the personal and professional lives of police officers, whose names flash across a TV screen or pop up on social media feeds across the country. The ultimate goal for police officers is to de-escalate a tense or potentially violent situation using as little force as possible in order to bring the event to a safe and successful conclusion. In order to maximize the ability for officers to avoid force, the Delta Police Department (DPD) has trained its entire sworn cadre in a technique called ICAT (Integrating Communications and Tactics).

March 14, 2019 By Norm Lipinski OOM MBA LLB

Why ICAT?

The DPD continues to see an escalation of “people in crisis” calls and although there is a myriad of possible reasons why the trend continues, the stark reality remains; some of these calls can be “high risk.” To clarify, “high risk” means physical, legal and emotional risk for all those involved. When officers are deployed to these calls, it is incumbent on leadership to ensure they are equipped with the best and most advanced tools — not necessarily physical tools — to bring high risk calls to a safe conclusion.

The courts have always ruled police officers should resolve conflict with the least amount of force necessary, but that is dependent on the equipment and training officers can rely on at the time of the call.

To that end, it would be prudent to have all frontline officers equipped with a conducted energy weapon (CEW) and a Less Lethal Launcher. However, when these calls occur, waiting for the appropriate equipment to arrive could be a missed opportunity to resolve the situation without anyone being hurt. With a supportive police board, the DPD is equipping the entire frontline with personal issue CEW and Less Lethal Launcher. However, even the use of less lethal tactics is a use of force option that should come after attempts to de-escalate a situation with communication.

Like most agencies across Canada, DPD has always focused on tactical skills, training and response, but an identified gap exists in the area of soft skills. Soft skills are the ability to talk a person out of crisis without a display of force or authority — to obtain compliance through dialogue.

How do we use ICAT?

After extensive examination across the globe, the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) has put together a program entitled Integrating Communications, Assessment and Tactics (ICAT). In March of 2017, DPD sent a combination of trainers and senior management to one of the PERF sessions, which proved to be very valuable. It allowed everyone to be on the same page as far as law, policy, training and ethics are concerned, while cementing an organizational commitment to this approach to de-escalation.

The DPD took the information garnered from that program, conducted further research and developed a home-grown model. Using the same acronym, the DPD simplified the title: Integrating Communications and Tactics (ICAT).

It is important to note that ICAT is best suited for those calls where an individual is acting erratically, is not mobile, and is not armed with a firearm.

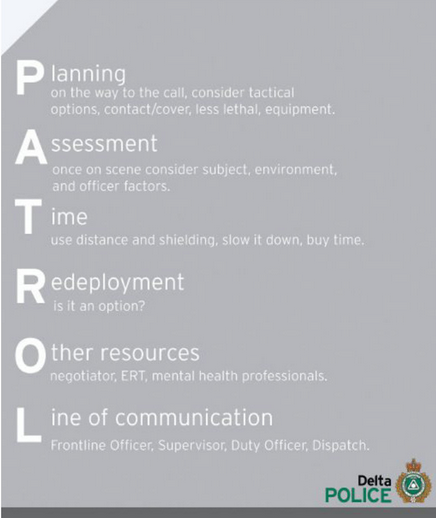

Since it will typically be uniformed officers responding to the call and planning should commence as information is being relayed, we found that the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) template was beneficial. The PATROL template serves as a guide for officers that ensures they are collecting all relevant information, considering all levels of tactics and communicating effectively to the rest of the team. The acronym PATROL makes it easier for officers to recall important aspects of a call, garnering greater buy-in at the front line:

Once an officer arrives on the scene and utilizes PATROL, how does he or she de-escalate?

In my view, not enough attention is paid to this issue both in recruit training and ongoing in-service training.

Having a junior officer respond to a suicidal person on a bridge and expecting them to communicate effectively, for perhaps a significant period of time, before a bona fide negotiator arrives is not a good scenario. What’s needed is training in the effective use of communication skills to calm the person down and reduce the probability of injury to that person and anyone else.

In order to bridge that critical gap of young officers waiting for trained negotiators, we worked with our Critical Incident Negotiators to modify the well-known LEAPS model. The model gives any responding officer a standard script to either slow things down or bring the crisis to a successful conclusion.

The DPD model includes the following six steps:

1. Introduction – Hello my name is… …I’m with the police and would like to help. What’s your name?

2. Listen – What happened? How can I help? (allow subject to talk)

3. Empathize – I see you’re upset, tell me about it.

4. Ask Open Ended Questions – Can you tell me more about that? Can I ask you to put the knife down? Can I ask you to step away from the railing?

5. Paraphrase – So what I hear you saying… …we can work this out together… nobody is going to hurt you.

6. Summarize – How about we/I help you (provide options/solutions)

The standard LEAP model does not include an official introduction, but we felt that by having an officer introduce themselves, it creates a personal relationship and opens up dialogue in a more natural way.

We win every fight we avoid, but I recognize that avoidance is not always possible. With verbal de-escalation, layered force options and appropriate training, this complete system has put us in a better position for the best outcome.

The training

Someone once said that repetition is the mother of skill and that is so true with ICAT.

As of January 2019, all DPD officers are trained in the concepts of ICAT and, more importantly, each officer takes the lead on at least three scenarios in the training. Yearly, there is a quick review and at least one scenario for every officer.

Real actors are used in the scenarios since the emotional component is very high. Also, each officer is advised simmunitions are not required in ICAT training. This allows for the freedom to talk without face protection and to be able to read facial expressions on the actor. Non-verbal communication, such as facial expression, is a key component of ICAT, and officers need to exercise the perishable skill of reading physical cues without encumbrances. Finally, all officers receive a plasticized card outlining the de-escalation steps that they can keep in their notebook for quick reference.

When police respond to a person in crisis, saving lives is of utmost importance. It is incumbent on police leaders to give all available tools to officers, particularly younger officers who are often the first to arrive on scene. The starting point in ICAT is to put the frontline officers in a winnable situation. That means developing communication skills and tactics that maximize de-escalation in one cohesive, integrated package. ICAT does that.

Norm Lipinski, OOM, MBA, LLB, is the Deputy Chief Constable of the Delta Police Department, a role he has served since 2016, after serving for five years as an Assistant Commissioner with the RCMP and 33 years with the Edmonton Police Service. He is an Officer of the Order of Merit of the Police Forces and is Vice-President of the BC Association of Municipal Chiefs of Police and Co-Chair of the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police Law Amendments Committee. Reach him at nlipinski@deltapolice.ca

Print this page