News

The Long Arm of Political Control

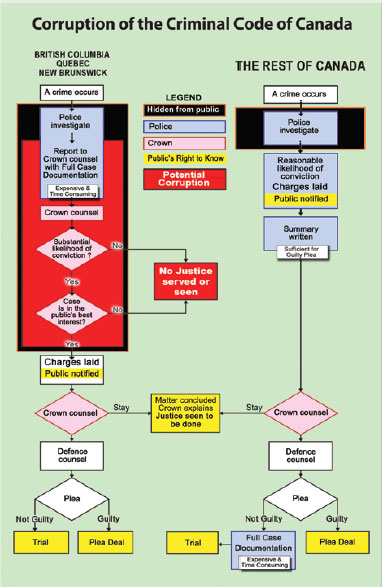

A stark lesson in both justice and democracy attached my focus on a serious defect in British Columbia's justice system. I have been tilting hard at this windmill for the last ten years, even running twice as an independent candidate in the provincial election – not to win but to use the public platform to systematically detail the damage caused by BC's corruption of the Criminal Code of Canada.

A pediatrician and serial child rapist abused a six-year old niece in the mid 90s. Our family sadly discovered that her case wasn't adjudicated because of systemic failures between the New Westminster police and Crown counsel office. Seeing firsthand this alarming failure to protect a child, I began working to fix the problems.

February 27, 2012 By Doug Stead

A stark lesson in both justice and democracy attached my focus on a serious defect in British Columbia’s justice system. I have been tilting hard at this windmill for the last ten years, even running twice as an independent candidate in the provincial election – not to win but to use the public platform to systematically detail the damage caused by BC’s corruption of the Criminal Code of Canada.

A pediatrician and serial child rapist abused a six-year old niece in the mid 90s. Our family sadly discovered that her case wasn’t adjudicated because of systemic failures between the New Westminster police and Crown counsel office. Seeing firsthand this alarming failure to protect a child, I began working to fix the problems.

BC’s Charge Approval (CA) legislation perverted the course of justice in the Tashie Case on Vancouver Island in early 2002. Police wanted to charge an Internet sexual predator but the Crown would not approve them. The point here is that the laying of the charge is also the point when the public has the right to know. I spoke about the investigation on a radio talk show and it became a public issue; suddenly charges were approved and the predator was convicted.

The point is, the crime must be seen for justice to be done. BC’s CA system hides it.

From a political perspective, the BC Crown Counsel Act has the advantage of allowing the attorney general, using unelected and unaccountable bureaucrats, to quietly control the cost of providing justice. It simply sets the number of courts and judges (closed court rooms) and Crowns have to triage crime to fit the restricted resources.

Justice is a core service. There is no underpinning legislation that allows a province to modify federal legislation, such as what BC has done with the Criminal Code.

An egregious example of how this unique BC legislation gerrymanders the Canadian justice system is the wrongful death of native Frank Paul. I believe charges were not approved in his 1998 death because the Crown of the day deemed it “NOT in the public’s best interest.” There is clear video proof of officers dragging Paul out of the building while he was incapacitated and leaving him in an alley to freeze. Despite this, the case did not go to court so the officers involved were not charged and the public was never notified of what had happened.

In the rest of Canada the only test applied – and only by police as provided in the Criminal Code – is the “reasonable likelihood of conviction by a jury of peers.” BC has changed “reasonable” to “substantial.”

My main concern is the tens of thousands of child sexual exploitation cases where the Crown has secretly allowed predators to avoid accountability. This is a really big issue – protecting children from sexual abuse and bringing sexual predators to justice.

The Crown Approval system

The Criminal Code is federal legislation which clearly gives police the authority and mandate to investigate crime and lay charges. This is how it works everywhere in Canada except BC and New Brunswick, both of which have enacted regulating policies that interfere with police authority. Interestingly enough both provinces brought in this gerrymandering soon after police did their jobs and laid charges against sitting provincial MLAs.

There is no underpinning legislative authority allowing provincial legislators to effectively bar police from swearing charges unless they are pre-approved by a provincial Crown. The effect is to use appointed civil servants to circumvent the Criminal Code, keeping the public from seeing justice being done – because the public only has a right to know after a charge has been sworn.

In all other jurisdictions Crowns can stay charges but only after they are laid and made public. In BC the Crown intervenes before charges are laid. This circumvents the public’s right to know and see what is happening. It also allows politicians to effectively manipulate the justice system by not proceeding with charges because it’s “not in the public’s best interest.” This can mean anything but usually indicates the Crown doesn’t have proper funding to proceed with expensive cases such as child exploitation, let alone a government employee who embarrasses the sitting government.

Brief history

Lawyers employed by BC municipalities at one time carried out prosecutions. The government established a Crown counsel system in 1974 and put the prosecution of criminal charges under the auspices of the Ministry of the Attorney General.

In the late 1970’s in New Westminster and Burnaby the practice arose of Crown counsel approving charges. Vancouver began doing this in April 1982. Prior to this the standard for charge approval was the existence of some evidence upon which a reasonable jury, properly instructed, could convict. This standard was changed in September 1983 to the current two-pronged one: Is there a substantial likelihood of conviction and, if so, is it in the public interest to proceed with the prosecution?

There does not appear to be any record of public discussion before the CA process and standard were adopted.

There was some examination of the practices. In December 1988, then deputy attorney general Mr. Justice Hughes concluded that charge approval ought to remain with Crown counsel (Access to Justice: The Report of the Justice Reform Committee). In order to address the system’s many reported difficulties, the Hughes Report recommended an appeal procedure making the deputy attorney general the final arbiter for CA. That procedure remains largely unchanged.

The CA process was again the subject of inquiry in 1990 when then ombudsman Steven Owen, Q.C. (later deputy attorney general) conducted the Discretion to Prosecute Inquiry. It canvassed the various positions advocating for and against the charge approval process.

The report concluded, in the absence of critical examination, that the process ought to continue but be based on a modified charge approval standard. The recommended standard would change the first fork of the test to the existence of a ‘reasonable likelihood of conviction.’ It was never adopted.

The BC Association of Chiefs of Police (BCACP) provided written briefs to both inquiries strongly arguing in favour of abandoning the CA process.

The police position

To maintain consistency, the Owen Report will also be used to articulate the positions advanced by police in 1990. It has been the consistent position of all BCACP members that the Crown Approval process ought to be abandoned and that BC ought not be the sole jurisdiction in the English speaking world burdened by the ‘substantial likelihood of conviction’ test for charge approval.

The five positions put forth were:

1. Erosion of police independence

The basis of this argument lies in the development of English common law. As the modern representatives of the public, police have both the right and duty to lay a charge where there are reasonable and probable grounds to believe an offence has been committed by identifiable person(s). This expressly recognizes the concurrent right and duty of Crown counsel to independently determine whether a charge should be prosecuted.

The traditional and usual system ensures that police are accountable to the public for the quality of their investigations and the objectivity of their decisions to lay charges. Information is a public document that assures those outcomes. The CA process does not allow that accountability.

By moving CA consideration off the public stage, both police and Crown are tainted by a non-transparent process opened to questions of bias and impropriety. In reality, entire classes of offences are not being prosecuted. This shows up in at least two places.

First, criminals know that the likelihood of prosecution for breach of probation and failure to appear offences is so remote that they flout the law with impunity. These are by no means the only offences so affected.

Secondly, police don’t expend resources investigating what the Crown won’t prosecute – and the public has learned not to report crimes that police won’t investigate.

The police independence argument is rooted in the position accepted by the vast majority of jurisdictions in Canada and around the world. The duties and prerogatives of the Crown are only engaged once a charge has been laid and not before. Recognition of the legitimacy of this position is found in case law (Campbell v. Attorney General of Ontario (1987), 31 CCC (3d) 289). The Marshall Commission of Inquiry has endorsed this position by recommending that:

Police officers be informed in general instructions from the solicitor general that they have the ultimate right and duty to determine the form and content of charges to be laid in any particular case according to their best judgment, subject to the Crown’s right to withdraw or stay the charges after they have been laid.

Since the Marshall Inquiry was examining one of the worst examples of a system gone wrong, this is a very strong, informed and compelling endorsement for police to retain charge approval.

Additionally, the position of police is mandated by legislation; as noted above, both the Criminal Code of Canada and the Crown Counsel Act of B.C. set out the basis. Conversely, the advocates for a CA process can cite no case law, inquiry, legislation or public discussion and acceptance of their position.

2. Minor offences

The basis of this argument cannot be put more succinctly or aptly than in the words of the Owen Report:

*The frequency with which minor offences are not prosecuted has three negative consequences. First, the victim and the public generally experience disenchantment with the criminal justice system. The public most frequently comes into contact with the criminal justice system through “minor” community crimes and they often have to retreat from their lawful enjoyment of public facilities such as beaches and parks because of the rowdiness and illegalities of others.

Second, this selective enforcement of the law fosters a disrespect for the law: citizens who are in other respects law-abiding question why they should obey the law if others who do not suffer no consequences for their illegal conduct.

Third, this attitude actually promotes crime; minor criminal offenders who see that the law is not enforced will recommit such offences and progress to more serious criminal activity… The policy of refusing to prosecute minor or nuisance crimes is shortsighted.*

The New York Police Department’s successes in reducing crime stand in stark contrast to Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

3. Potential for abuse

This argument reiterates points made above in relation to the essentially private nature of the CA process. In the absence of an information there is no public accountability and the decision making and propriety of police and Crown action is open to question. Indeed, the very need for the Decision to Prosecute Inquiry was a belated and expensive response to the public demand for accountability.

4. Usurping the role of the judiciary

There are two prongs to this argument in the Owen Report, while a third is found in the Criminal Code of Canada.

First, the initial test in the CA standard, the ‘substantial likelihood of conviction’, requires Crown counsel to determine matters of law, usurping the judiciary role to the extent they may not be settled or rely on the weight to be placed on particular elements of evidence.

Secondly, the various factors going into consideration of the public interest are precisely those normally encountered in discussions of sentencing principles. That consideration should be at the end of the criminal justice process, not at its invocation.

Thirdly, the Criminal Code provides for the preliminary hearing of many indictable offences. The standard of certainty demanded by the code and to be determined by a judge is decidedly less than a ‘substantial likelihood of conviction.’

5. Bureaucratic efficiency

This argument is founded on a CA process which requires police to prepare the full Report to Crown counsel (RTCC), forward it through some form of supervision process and then, after approval, back to police to swear the information. This system results in significant delays prior to a charge being laid and process issuing. This concern has been heightened, since the Owen Report, in the developing case law around unreasonable delay.

This process gives rise to an interesting illustration of Crown counsel picking and choosing what it does. The approving Crown is in precisely the same position as the court liaison officer when it comes to laying a charge – having access to precisely the same information. Crown determined the form and content of the charge, the sufficiency of the evidence and approved the charge. Why don’t they lay the Information?

Analysis and examples

• Statistical analysis

As observed above, a number of the putative benefits of the CA process are amenable to statistical proof. The statistics are uniquely available to the attorney general. Some relevant statistical data is also available from Statistics Canada. However mining that information is costly in both time and money.

The statistics presented above provide prima facie support for the police position.

Since the CA process and its corollary, the ‘substantial likelihood of conviction,’ are uniquely the creation of the BC Ministry of the Attorney General and since BC now has a 30-year history of that process, a call for the ministry to statistically validate its claims is entirely reasonable.

• Cost analysis

The CA process is initiated by a police officer putting together a full report to Crown counsel – in other jurisdictions this is commonly referred to as a court brief. This is extensive and includes all evidence, statements, records and other relevant items. In contrast, a simple prosecutor’s information sheet, or similar form, is used when police lay charges. It includes all relevant information sufficient to enable a judge to sentence an accused if they plead guilty.

It is only if an accused pleads not guilty that an officer would submit the full court brief. Since the majority of matters are disposed of by a guilty plea, considerable savings in police resource costs are realized when a full court brief is not required for all instances where police contemplate a charge.

In the CA process, Crown counsel are required to review 100 per cent of proposed charges. In the police-based process, Crown only have to consider charges where not guilty pleas are entered. Again, the police-based process represents savings, this time to the Crown counsel office.

• Other considerations

In addition to the points of view and arguments considered above, a number of issues have arisen in the recent past. Their impact and importance in relation to the CA process do not seem to have been examined elsewhere in any cohesive fashion.

Police accountability regimes

Since Owen examined this issue, there has been considerable development of regimes which insure the public accountability of police services. While this hasn’t always been smooth, all BCACP members welcome the opportunity to demonstrate, by transparent and open processes, how their services are fully accountable to the public they serve. Both the RCMP Act and Police Act of British Columbia contain effective provisions for accountability. Perhaps more importantly, the courts have taken on a highly active role under the auspices of the Charter in assuring the probity of police actions.

That the product of police service – the decision to lay a criminal charge – has been completely removed from police frustrates accountability regimes. That the actual decision is taken in private, absent any public discussion or record, runs entirely counter to public expectations.

Jane Doe implications

In the well-known Ontario case Jane Doe v. Board of Commissioners of Police for the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto et al., 39 O.R. (3d) 487 police were held liable to a sexual assault victim where they ought to reasonably have notified the public of a suspect’s pattern of behaviour. Two consequences flow from that decision in respect to charge approval.

Where the Crown declines to approve a charge that police have advanced, the duty to warn arises, triggered by a standard of belief well below that of reasonable and probable grounds. Police are then obligated to make a public warning about a person that the Crown declines to prosecute, serving neither Crown nor police well. That this situation hasn’t yet arisen is most likely because police are not generally aware that the duty to warn is not extinguished by the Crown’s decision not to lay charges.

The second implication revolves around the liability aspect of Jane Doe. Should a person be harmed by an individual who police have not warned the public about and the Crown has declined to charge, it is probable that the courts would find the police liable. Given the clear police duty to exercise their discretion in laying a charge, the likely finding would be that police unnecessarily fettered its discretion, notwithstanding the CA process. Also unconsidered by the courts to this point is the liability of the Crown in that situation. Having exercised a discretion that they do not have by law, do they then assume the liability?

The convenience argument

It has been argued that changing back to a police-based process would cause great inconvenience. This is founded on the fact that BC now has a 30-year history with the CA process and any return to police having charge approval would disrupt the business practices that have been developed.

Two arguments are available to refute that position. First, in no way can a case be made that the effective functioning of the criminal justice system should be predicated on either convenience or inertia. Secondly, it is in no way certain that reverting to the police-based system will do anything other than enable police to do more work, enabling the Crown to do more prosecuting – and more fully inform the public about what is really going on.

24 Hour JP centre

Court services unilaterally imposed this centre on both Crown and police in 2001. The chief judge of the provincial court has mandated the centre deal with search warrant, remand and related matters formerly dealt with by court registry and stipendiary JPs. Existing sitting JP’s and provincial court judges are prohibited from dealing with those matters absent exceptional circumstances. All dealings are by fax and/or phone.

Crown counsel have taken the position that their offices will not support matters the centre deals with. Consequently police have been forced into greater roles in more complex areas than the decision to lay a charge. Neither the courts nor Crown are troubled by that development. Police are deeply troubled by any number of systemic concerns with the new regime, including their ability to deal adequately with the new responsibilities.

A court recently arrived at its usual adjournment time with many matters still on the docket. The judge’s interesting solution was to simply close court and leave the lone police officer in attendance to deal with the remaining matters, by way of the telephone and JP centre.

Court closures

With the closing of 24 of BC’s existing 69 courthouses, fewer communities have Crown counsel. The ability to make ‘public interest’ distinctions on charge approval for communities Crowns are not familiar with will further exacerbate the existing difficulties with those decisions.

Abandoning the CA process alleviates this condition as police do remain in those communities.

Crown counsel cut

Announced with the court closures was a reduction in both ad hoc and staff Crown counsel. The delays currently experienced in charge approval will worsen. The daily experience of Crown counsel being unfamiliar with the file they are prosecuting will worsen. Abandoning the CA process alleviates both of these conditions.

Support for restorative justice initiatives

There is growing appreciation for the effectiveness of using restorative justice concepts in place of or to support the current criminal justice system. This development is similar to the acceptance of alternate resolution mechanisms in business disputes and mediation in family law matters. The inability to determine with certainty that a charge will be laid acts as an obstacle to police more widely implementing restorative justice practices.

Function creep

A number of experienced police officers have noted this problem. In some cases, Crown counsel are attempting to exercise a role more consistent with that of a US District Attorney in trying to direct and supervise active police investigations. This is an almost inevitable progression from a Crown-based CA system.

When police are not required to ultimately decide on the adequacy of their investigation to support a charge it is inevitable they will shy away from being responsible for decisions during the investigation and allow the Crown to occupy that field.

Conclusion and recommendations

The CA process contravenes:

• existing case law;

• the principle of police independence;

• the requirements of the Criminal Code; and

• the principles of public accountability.

The Crown Approval process has no legislative validity, adds costs and no benefits to the criminal justice system. Additionally it acts as an active impediment to dealing effectively with the reality of scarce resources and adopting innovative and effective community policing and restorative justice measures.

British Columbia must immediately abandon the CA process… and the rest of the country must take heed.

Print this page